ROMO

Monumental artist’s book

Edition of 12

Number of impressions: 28

The book comes with a clamshell case

By Todd Anderson, Bruce Crownover, and Ian van Coller

Literary essay by Jeff Rennicke

Bookbinding by Rory Sparks

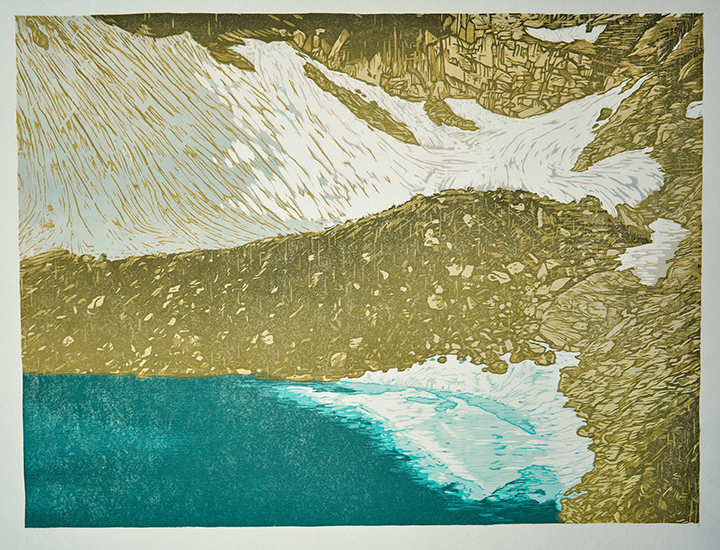

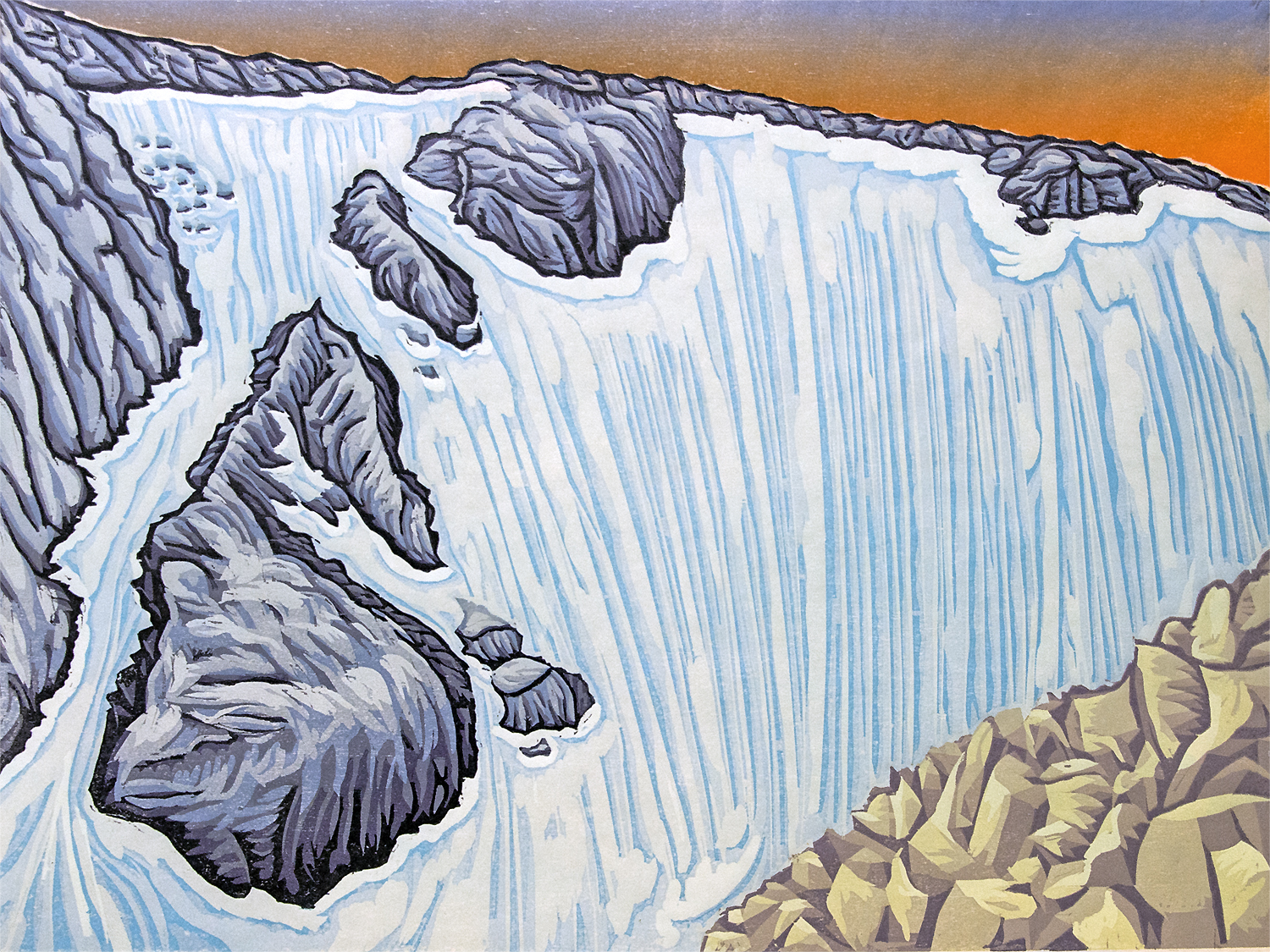

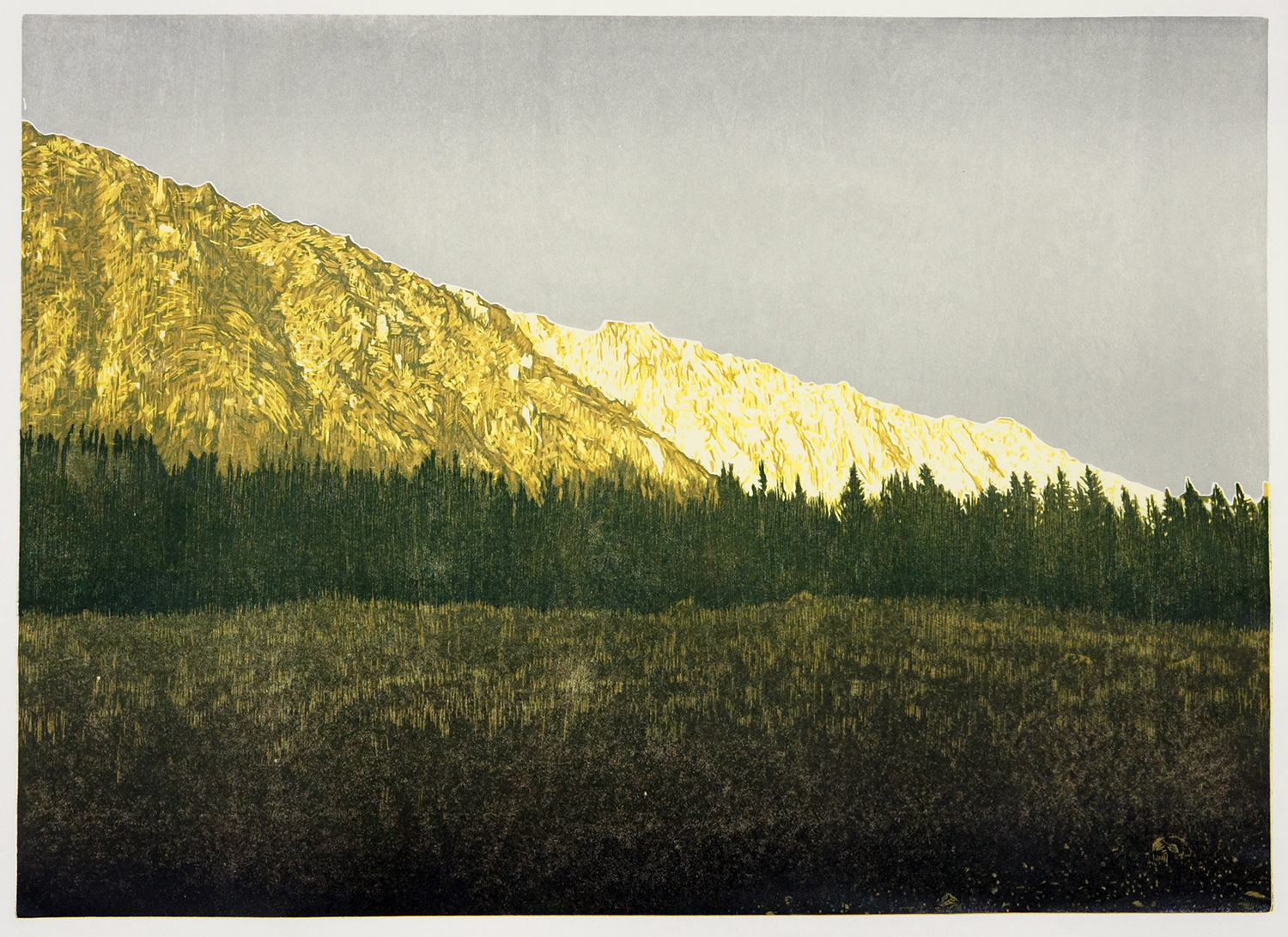

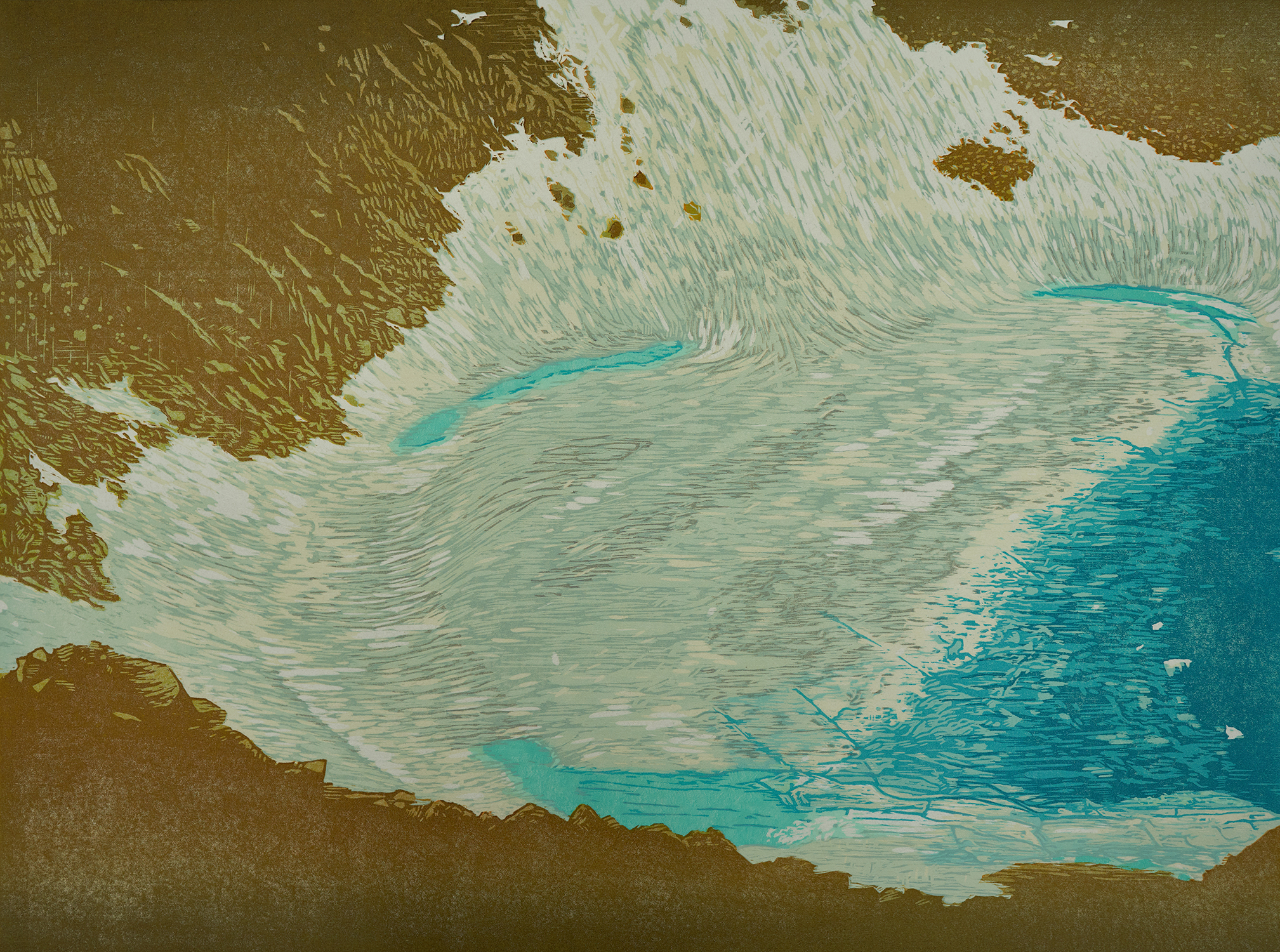

This is a monumental artist book (~17.5” x 46” inches when open, ~17.5” x 23” closed) of original woodcut prints and photographs that document the last glaciers in Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado, USA. All woodcut prints and printing of woodcuts are by Todd Anderson or Bruce Crownover. All photographs and printing of photographs are by Ian van Coller. “ROMO” is the governmental abbreviation for Rocky Mountain National Park.

This book is being released in the Summer of 2020. Special pre-publication pricing available upon inquiry.

Essay

The Dance of the Landscape

By Jeff Rennicke

A wind, a kind of low howl, rolls down the valley carved by the Tyndall Glacier deep in Rocky Mountain National Park. The glacier itself, what is left of it, sits like the shard of a fallen star just a few minutes scramble up the rocky slope. Catching my breath, I pick a pair of small, ice-rolled stones from the rubble at my feet. The stones click softly in my hand as I hike, a sound like a ticking clock.

Tyndall is one of just a handful of cirque glaciers left in the park, a landscape shaped by the repeated surge and retreat of ice. During glaciations with names like Bull Lake (125,000 to 50,000 years ago) and Pinedale (29,000 to 7,600 years ago), ice like bolts of frozen lightning flickered down the mountains and melted back leaving their artistry in moraines and eskers and U-shaped valleys. Ice carved this park; now the last of these great chiselers of landscapes may be about to vanish.

The footfalls of bighorn sheep, the clatter of stones, the nodding “yes, yes, and yes” of mountain avens in the breeze. This land is never still. Nothing in nature is. Glaciers are defined by movement––ice that moves is a glacier, that which doesn’t is an icefield. It is part of the dance of the landscape. But something else is happening here.

Climate change is disrupting the dance. Average temperatures in the park have increased by 3.4 degrees Fahrenheit (1.89 Celsius) in the last century. Wildfires have been sparked more often in the last 10 years than in the preceding 100. Snowpack has been below average more often than not since 2000.

What this means for the glaciers in the park is difficult to say. They are not well studied. They sit, for the most part, in small, north-facing pockets at high elevations like jewels set high in a crown and they are fed, not just by falling snow but by blowing snow riding westerly winds. For now, they are holding their own, not significantly growing or receding. But there is little doubt in the trend lines; science says these glaciers are in danger of vanishing before our eyes.

In ROMO, the photography of Ian van Coller, the woodcuts of Todd Anderson, and the abstracts of Bruce Crownover take us beyond the science and into art. Art will never replace the glaciers, nor is this book the ultimately futile effort to record the glaciers before they are gone. No brushstroke can capture the soprano notes of rivulets of ice melt trickling between the rocks. No wood cut or click of the shutter can fully express the softness of sublimation fog on your face or the smell of powdered rock where the ice has been at work. This book is not a stand-in for the glaciers. It is a jumping off point. A springboard to the imagination. And, a reminder of what we stand to lose.

I reach the brittle snout of the ice and find a spot behind a boulder out of the wind. The human mind struggles to put meaning in tens or hundreds of thousands of years, but to sit next to a glacier, even just for an afternoon, is to be in the presence of patience, persistence, and sublime power. It is to see time written in rock and ice. We need places like this, places where the stretch of time outreaches the horizons of human lives, if only for the way they remind us again and again of the immensity of the world we live in and the humbleness of our place in it.

A cloud dims the sun. A restless wind swirls. From below, I hear the plinking of ice melt moving downslope. The only other sound, for as long as I sit in the presence of what remains of the Tyndall Glacier, is a pair of ice-worn rocks clicking softly in my hand.